I am honored to be here today, and to be a part of this conference's 20th anniversary. A 20th anniversary is particularly meaningful to me as Director of FinCEN, as our agency celebrated our 20th anniversary only two years ago.

And while the focus of my remarks will be about how the anti-money laundering environment has evolved over these past 20 years, I think it is important to lay the groundwork for our discussions this morning by quickly looking back even further to the beginning.

The Evolution of AML Regulations

In 1970, Congress passed the Currency and Financial Transactions Reporting Act of 1970, the nation's first and most comprehensive anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing (AML/CFT) statute.1FinCEN implements, administers, and enforces this Act, as amended over the years; and all of you are probably more familiar with its more common description as the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA). And please allow me to quote directly from the Act: "It is the purpose of this chapter to require the maintenance of appropriate types of records and the making of appropriate reports by such businesses in the United States where such records or reports have a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations or proceedings."2The Secretary of the Treasury has delegated administration of the BSA to FinCEN.

And as George P. Schultz, Secretary of the Treasury from 1972-1974, noted in a document accompanying the regulations implementing the Financial Recordkeeping and Currency Transactions Reporting Act of 1970:

Every effort has been made to ensure that the final regulations will serve their law enforcement purposes, while at the same time not interfere with legitimate international monetary transactions, unduly burden financial institutions or others, or impose unreasonable requirements that would serve no useful purpose. In doing this, consideration has been given to existing recordkeeping procedures, including the length of time records are ordinarily retained.

And this "balance" that Secretary Schultz first spoke of more than three decades ago, continues to be at the heart of how FinCEN has approached AML regulations.

Shortly after its enactment in 1970, the constitutionality of the BSA was challenged by several parties, including individual bank customers, a major bank, a trade association, and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Those plaintiffs argued, among other things, that certain BSA reporting and recordkeeping requirements deprived the banks of due process by imposing unreasonable burdens upon them and that currency transaction reporting amounted to an unreasonable search of customers' financial transactions. In a 1974 decision styled California Bankers Association v. Shultz3, the Supreme Court rejected these arguments, holding that the "cost burdens imposed on the banks . . . are far from unreasonable" and that the reports required under the BSA are "reasonable in light of [their] statutory purpose."4

Two years later, in its Miller decision, the Court rejected another constitutional challenge to the BSA. That case involved a man who was convicted, in part, on the strength of copies of checks and bank deposits maintained to comply with the BSA. The man argued that he had a Fourth Amendment interest in those bank records and that they were illegally seized. The Court rejected this argument, holding that customers do not have Fourth Amendment privacy rights in their financial records maintained by a financial institution.5Ironically, the Court's holding in Miller was the main impetus for the enactment of the Right to Financial Privacy Act two years later.

The Money Laundering Control Act of 19866established money laundering as a Federal crime; prohibited structuring transactions to evade currency transaction report (CTR) filings; introduced civil and criminal forfeiture for BSA violations; and directed banks to establish and maintain procedures to ensure and monitor compliance with the reporting and recordkeeping requirements of the BSA.

In 1990, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, known as FinCEN, was established by then-Secretary of the Treasury Nicholas Brady.7In the beginning, FinCEN was an office within the Department of the Treasury.8It was under the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001, however, that its functions were statutorily formalized as a bureau within the Treasury Department.9FinCEN's responsibilities to receive, analyze, and disseminate financial intelligence for AML/CFT purposes and to coordinate with foreign financial intelligence units (FIUs) were codified into law.10

FinCEN was created to be the bridge between law enforcement agencies and the financial industry. Our prescient designers saw the need for a central repository of financial intelligence that would collect, protect, and analyze the valuable information that industry could provide and then share it with law enforcement agencies, which at the time were holding several disparate and unconnected databases of their own. At the time a novel concept, the connections that FinCEN made, and the investigatory efficiency it provided, allowed users of the data to avoid duplicative efforts and to target their resources more effectively.

In 1993, FinCEN established Project Gateway, a program enabling State and local law enforcement agencies to access FinCEN reports for use in their investigations. By 1994, 45 states plus the District of Columbia had begun accessing the data through this system.

Today, there are currently more than 12,000 nationwide users of the information at all levels of the law enforcement and regulatory communities.

In 1994, FinCEN also opened its doors to law enforcement agencies who wished to come to our office to access the FinCEN data. Our Platform Program provides on-site access to FinCEN systems for designated personnel in the Washington, D.C. area who are conducting research for their agency's investigations. Currently, 42 Federal law enforcement agencies participate in this program, including offices of the Inspector General, which work to uncover waste, fraud, and abuse in government programs.

FinCEN's systems also provide us with alerts when more than one agency is researching the same subject within the FinCEN data. Last year alone, FinCEN networked agencies together more than 1,000 times by contacting investigative personnel in the respective agencies and providing them contact information for other agency personnel performing similar data searches.

In 1992 the Annunzio-Wylie Anti-Money Laundering Act required financial institutions to report suspicious activity on Suspicious Activity Reports, and eliminated previously used Criminal Referral Forms (CRFs).11

The Annunzio-Wylie Anti-Money Laundering Act also strengthened the sanctions for BSA violations and required verification and recordkeeping for wire transfers. Further, the Act established the Bank Secrecy Act Advisory Group (BSAAG), to provide a key forum for FinCEN's domestic constituencies to discuss pertinent issues and to offer feedback and recommendations for improving BSA records and reports.12

As then-Secretary of the Treasury Lloyd Bentsen said when announcing the formation of the BSAAG in March 1994, "We must keep money launderers out of our financial institutions and businesses. The group's work will greatly expand the Department's review of its regulations and anti-money laundering programs." Bentsen also noted that Treasury would continue its "commitment to reduce the Department's reporting burdens while simultaneously ensuring that law enforcement officers be able to spot and track suspicious transactions."

At that first meeting there were 30 members, comprised of representatives from the banking industry, as well as Federal and State government officials. Over the years, the composition of the BSAAG has adapted and changed to reflect the growing role of other types of financial institutions beyond banks. For the 37th meeting of the BSAAG taking place at the U.S. Department of the Treasury next week, 54 members (nearly double the original group) will be participating from not only banks, but there will be representatives from industries such as: insurance, casino, precious metals, broker dealers and securities, prepaid cards, and money services businesses.

Keep in mind that at the time of the first BSAAG meeting in April 1994, FinCEN was still working with its Federal regulatory partners to create a suspicious activity reporting system to replace the use of Criminal Referral Forms, as mandated by the Annunzio-Wylie Anti-Money Laundering Act of 1992. At this point, banks were required to report suspicious activity by filing multiple copies of CRFs with their respective Federal regulators as well as law enforcement agencies. Banks were also encouraged to report this activity by filing a CTR and checking a box to mark it as "suspicious." These multiple filings imposed a burden not only on banks, but on law enforcement agencies, which struggled to correlate the multiple filings and avoid overlap and confusion in their investigations.

In reviewing the minutes from that first meeting, this topic was actively discussed by the BSAAG members. Two approaches that were considered at the time were to (1) create a suspicious CTR that would ask for a narrative about the suspicious conduct; and (2) devise a uniform report to be filed by banks and non-banks.

Reporting by Financial Institutions

So even from those first BSAAG meetings, issues surrounding the filing of CTRs, along with discussions of how to more effectively file reports of suspicious activity, were taking place. Allow me to provide some perspective on the volume of information that financial institutions report. Looking back over the past nine years, the number of CTRs filed each year has averaged about 14 million. Over this same time period, an average of about 168,000 Reports of International Transportation of Currency or Monetary Instruments (CMIRs) were filed each year, and an average of 167,000 Form 8300s were filed each year.

And just a little more than a year after the first BSAAG meeting, in September 1995, FinCEN proposed simplified rules for reporting suspicious activity that would create "a single centralized system for the reporting of suspicious transactions and information on known or suspected criminal violations involving financial institutions."13As the news release stated, "the proposed regulation is the centerpiece of Treasury's effort to change the focus of BSA anti-money laundering measures from the mechanical reporting of millions of large currency transactions to the judicious reporting of relatively fewer, but more significant, suspicious transactions." And as former FinCEN Director Stanley E. Morris said at the time, "The end result is a single, automated process and database which will not only reduce the regulatory burden on the banking community, but also greatly increase the usefulness of information provided to the government and industry." In February 1996, final rules were issued,14which went into effect on April 1, 1996.

The foundation for what has become our current suspicious activity reporting process had begun. And the definition of "financial institution" would evolve over the years as well. As I will discuss shortly as it relates to the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001, anti-money laundering program and suspicious activity reporting requirements were expanded in the past decade to include all appropriate elements of the financial services industry, and to close regulatory gaps.

| Financial Industry | SAR Effective Date |

|---|---|

| Depository Institutions and Credit Unions | April 1996 |

| Money Services Businesses | January 2002 |

| Casinos and Card Clubs | October 2002 |

| Brokers and Dealers in Securities | January 2003 |

| Currency Dealers and Exchangers | March 2003 |

| Futures Commission Merchants and Introducing Brokers in Commodities | December 2003 |

| Insurance Companies | December 2005 |

| Mutual Funds | June 2006 |

| Prepaid Access | September 2011 |

| Residential Mortgage Lenders and Originators | April 2012 |

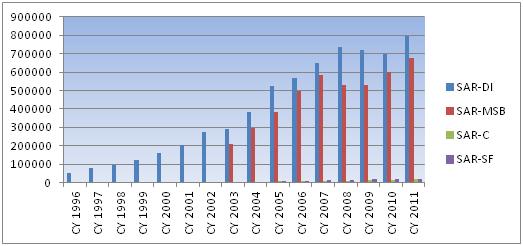

This chart reflects the volume of suspicious activity report (SAR) filing since 1996, and reflects the inclusion of SARs filed beyond depository institutions, to explain for the growth in the overall number of SAR filings over the years. In total, between 2003 and 2011, more than 5.3 million SARs were filed by depository institutions; 4.3 million by money services businesses; 89,000 by casinos; and 110,000 by the securities and futures industry.

With this volume of reporting, it became evident early on that requiring financial institutions to file reports that are of little use to law enforcement is to no one's benefit. It costs financial institutions time and money, and makes it more difficult for law enforcement to focus in on the reports that are of the most relevance.

The Money Laundering Suppression Act of 1994 (MLSA) amended the BSA by authorizing regulations exempting transactions by certain customers of depository institutions from currency transaction reporting.15

In April 1996, FinCEN announced its first efforts to begin reducing the number of CTRs that were filed by financial institutions, in order to decrease unnecessary paperwork for America's banks and improve the quality of information routinely provided to law enforcement.16FinCEN issued exemption regulations in two phases, specifying the criteria under which a bank may take advantage of the exemption authority.17Under Phase I exemptions, transactions in currency by banks, governmental departments or agencies, and public or listed companies and their subsidiaries are exempt from reporting.18Phase II allows depository institutions to exempt from reporting transactions in currency between it and "non-listed businesses" or "payroll customers."19

In 2008, FinCEN moved even further to simplify the requirements for depository institutions to exempt their eligible customers from currency transaction reporting,20based on Government Accountability Office's (GAO's) recommendations21as well as FinCEN's independent research on the underlying issues. As the GAO highlighted in its February report, Currency Transaction Reports (CTRs) provide unique and reliable information essential to supporting investigations and detecting criminal activity.

The final rule, which went into effect in January 2009,22made the following changes to the CTR exemption system:

- Depository institutions are no longer required to review annually or make a designation of exempt person (DOEP) filing for customers who are other depository institutions, U.S. or State governments, or entities acting with governmental authority;

- Depository institutions are able to designate an otherwise eligible non-listed company or a payroll customer after either two months time (previously twelve months) or after conducting a risk-based analysis of the legitimacy of the customer's transactions;

- FinCEN's guidance on the definition of "frequent" transactions was changed to five transactions per year instead of the then current eight transactions per year;

- Depository institutions are no longer required to biennially renew a DOEP filing for otherwise eligible Phase II customers, but an annual review of these customers must still be conducted; and

- Depository institutions are no longer required to record and report a change of control in a designated non-listed or payroll customer.

And in June 2007, in order to provide relief to casinos from reporting transactions relating to jackpots from slot machines and video lottery terminals, which due to their nature are not likely to form part of a scheme to launder funds through casinos, a final rule was issued that exempts casinos from the requirement to file CTRs on jackpots from slot machines and video lottery terminals.23This highlights the regulatory efficiency and effectiveness that can be reached through outreach with the industry on the mutual goal of improving the reporting requirements to make appropriate information available to law enforcement users.

It is important to note that even with all of our efforts to streamline the CTR exemption process, and taking into consideration that the Currency and Financial Transactions Reporting Act of 1970 focused on cash reporting, even today - with incredible advances in technology used to transmit payments - we continue to see a significant amount of criminal cash issues.

In 1998, the Money Laundering and Financial Crimes Strategy Act required banking agencies to develop anti-money laundering training for examiners. The Act also required the Department of the Treasury and other agencies to develop a National Money Laundering Strategy, the first one of which was issued jointly by the U.S. Departments of the Treasury and Justice in 1999.24As noted in the foreword of the Strategy:

The Strategy marks a new stage in the government's fight against money laundering. It is a battle that the government has been waging for many years, both at home and abroad, and in which there has been significant progress on the law enforcement as well as the regulatory side. But the Strategy inaugurates a new level of coordination and cooperation: across the agencies of the federal government, among federal, state and local authorities, and between the public and private sectors.

The Money Laundering and Financial Crimes Strategy Act also created the High Intensity Money Laundering and Related Financial Crime Area (HIFCA) Task Forces to concentrate law enforcement efforts at the Federal, State, and local levels in zones where money laundering is prevalent.25HIFCAs may be defined geographically or they can also be created to address money laundering in an industry sector, a financial institution, or group of financial institutions.

FinCEN has had analysts serving as liaisons at various HIFCA locations since 2000. Currently, HIFCA liaisons are located in San Francisco, New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, and the Southwest border. These FinCEN staff support investigations and law enforcement initiatives in their areas by providing analytical support based on FinCEN data. They work with the SAR review teams and task forces in their locations, regularly review SARs, and make presentations to law enforcement on the use of SARs and other data reported under FinCEN's regulations.

Also in 2000, as part of the overall need to update and tailor the application of the Bank Secrecy Act to a significant part of the financial sector beyond banks, the foundation was laid for Money Services Businesses (MSBs), which until this time were only required to file CTRs, to also become subject to SAR filing requirements.26Specifically, the amendments to the BSA required money transmitters and issuers, sellers, and redeemers of money orders and traveler's checks to report suspicious transactions to FinCEN. As stated in the final rule, "The amendments constitute a further step in the creation of a comprehensive system (to which banks are already subject) for the reporting of suspicious transactions by financial institutions. Such a system is a core component of the counter-money laundering strategy of the Department of the Treasury."

The effective date for SAR reporting by MSBs would ultimately be January 1, 2002,27although many MSBs would begin filing voluntary SARs well in advance of this date.

But turning back to the fall of 2001, and what was arguably one of the most significant events not only in our country's history, but certainly in the AML world. As we all know, the world changed for all of us on September 11, 2001. At FinCEN, law enforcement support operations went into a 24/7 cycle, in order to provide real-time assistance in the weeks and months to follow. FinCEN also established a hotline for financial institutions to report to law enforcement suspicious transactions that might have been related to the terrorist attacks.28

Also in response to the attacks, on October 26, 2001, Congress passed the Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools to Restrict, Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act of 2001, commonly known as the USA PATRIOT Act.29

The purpose of the USA PATRIOT Act is to deter and punish terrorist acts in the United States and around the world, to enhance law enforcement investigatory tools, and other purposes, some of which include:

- To strengthen U.S. measures to prevent, detect, and prosecute international money laundering and the financing of terrorism;

- To subject to special scrutiny foreign jurisdictions, foreign financial institutions, and classes of international transactions or types of accounts that are susceptible to criminal abuse;

- To require all appropriate elements of the financial services industry to report potential money laundering;

- To strengthen measures to prevent use of the U.S. financial system for personal gain by corrupt foreign officials and facilitate repatriation of stolen assets to the citizens of countries to whom such assets belong.

Title III of the USA PATRIOT Act is referred to as the International Money Laundering Abatement and Financial Anti-Terrorism Act of 2001. In addition to establishing FinCEN as a bureau within the U.S. Department of the Treasury, Title III also:

- Criminalized the financing of terrorism and augmented the existing BSA framework by strengthening customer identification procedures;

- Prohibited financial institutions from engaging in business with foreign shell banks;

- Required financial institutions to have due diligence procedures and, where necessary, enhanced due diligence procedures for foreign correspondent and private banking accounts;

- Improved information sharing between financial institutions and the U.S. government by requiring government-institution information sharing and voluntary information sharing among financial institutions;

- Expanded the anti-money laundering program requirements to all financial institutions;

- Increased civil and criminal penalties for money laundering;

- Provided the Secretary of the Treasury with the authority to impose "special measures" on jurisdictions, institutions, or transactions that are of "primary money laundering concern;"

- Facilitated records access and required banks to respond to regulatory requests for information within 120 hours;

- Required Federal banking agencies to consider a bank's AML record when reviewing bank mergers, acquisitions, and other applications for business combination.

A proud day in FinCEN's history, amidst the sobering events of that fall, was a visit by President George Bush to FinCEN's headquarters offices in northern Virginia in November 2001. The President came to FinCEN, alongside Secretary of the Treasury Paul O'Neill, Secretary of State Colin Powell, Attorney General John Ashcroft, and FinCEN Director James Sloan, to announce a crackdown on a terrorist financial network, and noted in his remarks, "I want to thank the (FinCEN) Director, Jim Sloan, as well. You're doing some imaginative work here at the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, and I want to thank all the fine Americans who are on the front line of our war, the people who work here." 30

As I noted a few moments ago, the USA PATRIOT Act expanded the anti-money laundering program requirements to all financial institutions.31In the months following the passage of the USA PATRIOT Act, in April 2002, FinCEN published regulations requiring some of those financial institutions to implement AML programs, including (1) mutual funds; (2) operators of credit card systems; (3) money services businesses, such as money transfer companies and check cashers; (4) securities brokers and dealers registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission; and (5) futures commission merchants and accompanying brokers registered with the Commodity Futures Trading Commission.32At this time, FinCEN also announced it would be exercising its authority to defer the remaining categories of financial institutions to allow time to study these new emerging sectors and develop regulations applicable to them.

Information Sharing

In a significant step toward increasing information sharing, FinCEN announced in February 2002 regulations to allow for information sharing as required under Section 314 of the USA PATRIOT Act.33Specifically, Section 314 of the Act bolsters the information exchange regime by enhancing two key channels for sharing information: (1) information exchange between law enforcement and financial institutions (Section 314(a)); and (2) information exchange among financial institutions (Section 314(b)).

Today, Section 314(a) of the USA PATRIOT Act enables Federal, State, local, and foreign law enforcement agencies, through FinCEN, to reach out to more than 45,000 points of contact at more than 22,000 financial institutions to locate accounts and transactions of persons that may be involved in terrorism or significant money laundering.

FinCEN receives requests from law enforcement agencies and upon review sends requests to designated contacts within financial institutions across the country generally once every two weeks via a secure Internet Web site. The requests contain subject and business names, addresses, and as much identifying data as possible to assist the financial institutions in searching their records.

The financial institutions must query their records for data matches, including accounts maintained by the named subject during the preceding 12 months and transactions conducted within the last six months, unless a different time period is specified in the request. Financial institutions typically have two weeks from the transmission date of the request to respond to 314(a) requests. If the search does not uncover any matching of accounts or transactions, the financial institution is instructed not to reply to the 314(a) request.

To date, financial institutions have responded with over 100,000 positive subject matches, 8,900 of which came from 440 institutions in California. And based on the total feedback we have received, 74 percent of 314(a) requests have contributed to arrests or indictments, demonstrating the high value of information these institutions are providing to law enforcement.

FinCEN's review of our data also shows that in the past five years, more than 60 percent of positive 314(a) matches have come from institutions with assets under $5 billion. In addition, FinCEN estimates that over the past five years, 92 percent of the institutions that have responded to 314(a) requests are institutions with assets under $5 billion.

The general proposition remains true that in absolute terms a very small depository institution is statistically less likely to be touched by organized criminal activity than depository institutions with millions of customers and tens or hundreds of billions in assets. But the 314(a) statistics alone have shown that in comparative terms a disproportionately high number of actual cases of terrorist financing and significant money laundering have involved accounts and transactions at smaller depository institutions. The 314(a) statistics underscore how important it is for all financial institutions, big and small, to assess risk and implement appropriate policies and procedures to mitigate risk.

Section 314(b) of the USA PATRIOT Act allows financial institutions to share information with each other for the purpose of identifying and, where appropriate, reporting possible money laundering or terrorist activity.

While participation in the Section 314(b) program is ultimately voluntary, FinCEN would like to emphasize the importance of information sharing in protecting the financial system from abuse.

FinCEN published guidance in June 2009 on the scope of the safe harbor provided by 314(b). The guidance clarified that a financial institution participating in the 314(b) program may share information relating to transactions that the institution suspects may involve the proceeds of one or more specified unlawful activities. The institution will still remain within the protection of the 314(b) safe harbor from liability. "Specified unlawful activities" under 18 U.S.C. 1956 and 1957 include a broad array of underlying fraudulent and criminal activity. If you are not among the 312 institutions in California currently sharing information through 314(b), I encourage you to do so.

E-Filing

Also in 2002, FinCEN took its first steps toward the electronic filing of certain FinCEN reports.34Prior to this point, financial institutions could file their reports either on magnetic tape or paper. Magnetic submission of FinCEN reports was phased out in 2008.

In the past decade, FinCEN has continued moving forward to promote its free, Web-based electronic filing system allowing filers to submit through a secure network their reports required under FinCEN's regulations implementing the BSA. And while it began in 2002 as a pilot program involving 26 financial institutions, approximately 8,000 financial institutions are now E-Filing with FinCEN.

And subject to certain exemptions and hardship extensions, all FinCEN reports must be E-Filed beginning July 1, 2012.35FinCEN had formally solicited comment on its proposal to require E-Filing. The benefits of E-Filing, both to the government and to the filer, are obvious and compelling. As more and more financial institutions migrate to E-Filing, they will be impressed with the ease and convenience of using their basic Internet connections, while gaining immediate feedback to continually improve the quality and usefulness of the reported information in the effort to combat financial crimes.

With the July 1 date approaching, FinCEN has been working closely with our state and Federal counterparts to increase outreach to those financial institutions who have submitted paper reports in the last few months to ensure industry is prepared for mandatory E-Filing.

One final point: greater use of E-Filing also assists FinCEN in providing important information relevant to money laundering and terrorist financing investigations to law enforcement in the quickest manner possible. Through E-Filing, reports are available to and searchable by law enforcement in two days, rather than two weeks, for example if filed on paper.

Efficiency and Effectiveness

In March 2007, standing alongside then-Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson, I announced we would be taking a fresh look at the way FinCEN carries out its mission. This included a review of the regulatory framework with a renewed focus on ensuring that requirements on covered financial industries are efficient in their application, yet remain extremely effective in their service to law enforcement investigators, FinCEN analysts, and regulatory examiners, to safeguard the financial system from the abuses of terrorist financing, money laundering, and other financial crime.

I made the commitment in June 2007 to conduct analyses and provide public written feedback within 18 months of the effective date of a new regulation or significant change to an existing regulation. Since that time, FinCEN has published multiple assessments as part of this commitment, to test whether a regulatory change once implemented is achieving its intended purpose. These assessments can all be found on the Regulatory Efficiency and Effectiveness page on FinCEN's Web site.36

For example, I spoke earlier of our work to further streamline CTR exemptions and our most recent rule that went into effect in January 2009 to simplify the process. In keeping with our 18-month "look back" commitment, in July 2010, FinCEN issued an assessment of how this rule change impacted DOEP filings.37As noted in the report:

The positive effects of those changes are most clearly reflected in the number and type of DOEP filings. Overall, FinCEN found that DOEP filings fell 44 percent to the lowest levels ever. Since the rule made DOEP filings unnecessary when the subject is a bank, government agency, or governmental authority, those filings dropped nearly 75 percent in 2009. Those filings should eventually fall to zero, and measuring them is a good indication of the rule's effectiveness.

The rule change retained the initial DOEP filing requirement for certain other customers where FinCEN deemed the DOEP filing would still provide useful information for law enforcement, but significantly reduced the thresholds and simplified the process for making those designations. As a result, the number of initial DOEP filings for these types of customers grew 41.7 percent in 2009, indicating that many institutions understood and were taking advantage of the new streamlined exemption process.

President Obama has underscored the importance of retrospective analysis of existing rules among other obligations to ensure that the benefits of regulations outweigh the costs, even in those cases where they are difficult to quantify. The theme of cooperation between government and regulated industry, including through the President's Open Government Initiative, will continue to be an essential part of the good government process, as future plans for regulatory review are developed and implemented.38FinCEN consistently emphasizes the importance of partnership with financial institutions in achieving its shared goals of rooting out financial crime.

Another initiative related to efficiency and effectiveness is our commitment to improve consistency across different regulated sectors. March 1 of this year marked the first anniversary of the effective date upon which our rules and regulations were reorganized within a new Chapter X of Title 31 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR).39The reorganization streamlines the BSA regulations into general and industry-specific Parts, making the regulatory obligations clearer in their structure, more consistent, and more accessible to affected financial institutions. Chapter X helps all financial institutions identify their obligations under the BSA in a more organized and understandable manner, which in turn improves compliance.40

Regulatory Partnerships

In FinCEN's earliest days, our regulatory partnerships primarily existed with the Federal banking agencies. With the advent of SAR reporting, and the expansion of AML program and SAR reporting requirements to other financial industries, our regulatory partnerships grew to include the Securities and Exchange Commissioner and the Commodities Futures Trading Commission. And in June 2005, FinCEN began the process of entering into Memorandum of Understanding with State banking agencies across the country to enhance collaboration and information sharing between Federal and State agencies and assist State agencies to better fulfill their roles as financial institution supervisors.41

FinCEN has also worked closely with our State and Federal regulatory counterparts on examination manuals, both for banks and credit unions,42and for money services businesses.43The manuals provide current and consistent guidance on risk-based policies, procedures, and processes for Federal and State examiners, and the guidance on regulatory expectations is a valuable resource for financial institutions as well.

And included as part of the Fiscal Year 2013 budget proposal, the Administration has proposed a legislative amendment to FinCEN's statutory authorities that would allow for reliance on examinations conducted by a State supervisory agency for categories of institutions not subject to a Federal functional regulator.44This would capture most non-bank financial institutions currently subject to IRS examination as delegated by FinCEN by regulation and a Memorandum of Understanding. If Congress agrees, FinCEN will be able to pursue a new level of cooperation with States on examination issues, so we will explore that going forward.

International growth

Only five years after FinCEN was established, in June 1995, FinCEN Deputy Director William Baity, along with representatives from a small group of government agencies and international organizations gathered at the Egmont-Arenberg Palace in Brussels to discuss money laundering and ways to confront this global problem. This was the first meeting of what has now become known as the Egmont Group. They established a Legal Working Group to examine obstacles to the cross-border exchange of financial intelligence. In 1996, they adopted a definition of an FIU (slightly revised in 2004 to extend the focus from money laundering to explicitly reference terrorism financing):

A central, national agency responsible for receiving, (and as permitted, requesting), analysing and disseminating to the competent authorities, disclosures of financial information:

(i) concerning suspected proceeds of crime and potential financing of terrorism, or

(ii) required by national legislation or regulation, in order to combat money laundering and terrorism financing.45

The few agencies in place that acted more or less consistently with this definition continued meeting on an informal basis after the 1995 gathering in what became known as the "Egmont Group." The FIU concept has grown over the years and is now an important component of the international community's approach to combating money laundering and terrorist financing. To meet the standards of Egmont membership an FIU must be a centralized unit within a nation or jurisdiction to detect criminal financial activity and ensure adherence to laws against financial crimes, including terrorist financing and money laundering.46

The establishment of the Egmont Group of FIUs in 1995 led to the promulgation of operational standards and expectations. As a reflection of the growing importance of FIUs, consider that the Egmont Group's membership has expanded from just 15 FIUs in 1995, to 53 in 2000, to 127 in 2011, with additional jurisdictions preparing to join later this year. During the past 17 years, the Egmont Group has developed mechanisms for the rapid exchange between FIUs of sensitive information across borders. The Egmont Group members have agreed upon a common framework for information exchange. This framework begins with a shared vision - an internationally accepted definition - of an FIU that serves as a national, central authority that receives, analyzes, and disseminates disclosures of financial information, particularly suspicious transaction reports (STRs) to combat money laundering and terrorist financing.47

That Egmont definition of an FIU was incorporated as one of the more significant revisions of the FATF Recommendations in 2003. And in February of this year, the FATF Recommendations were further revised, and as stated in FATF's press release announcing the revisions, one of the main changes is "Better operational tools and a wider range of techniques and powers, both for the financial intelligence units, and for law enforcement to investigate and prosecute money laundering and terrorist financing."48

The most recent revisions draw further upon the Egmont practices as well as aspirations for the role strengthened FIUs should play in global AML/CFT efforts of the future. The most prominent changes are the increased emphasis on analysis as the core function of FIUs, and on access to relevant information - in particular the new element that the FIU be able to obtain additional information from reporting entities.

And regarding an FIU's analytical functions, the revised FATF interpretive note now states: "FIU analysis should add value to the information received and held by the FIU."49The interpretive note underscores the importance of FIUs conducting both operational analysis focusing on particular targets of investigative interest, and strategic analysis, to identify money laundering and terrorist financing related threats and vulnerabilities.50The note draws upon the Egmont definition of analysis, which describes different stages and forms of analysis, including reflecting the differing volumes of reports a particular FIU might receive.51

One other example of a less extensive change to the Recommendations that I will nonetheless mention for the international audience here today is a more explicit statement that financial groups should be required to implement group-wide AML/CFT programs, including policies and procedures for sharing information within the group for AML/CFT purposes.52

The future

As FinCEN's work has evolved, so has the size of our bureau. In its earliest days, in 1991, FinCEN had 196 employees.53A decade later in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, and in the first year that FinCEN was a bureau, this number had increased only slightly to 205.54In the years following 9/11, as FinCEN's responsibilities continue to grow, FinCEN's workforce increased by fiscal year 2009 by nearly 60 percent, to 327.55In fiscal year 2011, FinCEN's employees totaled 303.56While many challenges and opportunities remain, throughout government we are called upon to do more with less. Here is where FinCEN can continue to excel by leveraging insights, information, and solutions across so many different agencies at the Federal, State, local and international levels

As we look to the future, we must always be aware of the past and seek to build upon the foundation of those before us. While technology and financial services rapidly evolve, so do criminal attempts to abuse them. Amidst this change, certain things remain steady. The core thinking of the prescient founders of FinCEN remains more pertinent than ever. Our focus must remain on serving our law enforcement customers in our unique area of expertise in following the money, as money motivates or facilitates virtually all criminal activity. And in an increasingly globalized world, FinCEN's ability to transcend borders through its FIU connections is only becoming more important.

On the regulatory side, we will also continue to evolve. Not just in a broadening of financial sectors covered as in the past, but more so in a deepening sense in focusing on better implementation and compliance. FinCEN's most recent rules - with respect to prepaid access and non-bank mortgage lenders and originators portend some aspects of the future: closing regulatory gaps and drawing insights from our analysis and support of criminal case investigations to learn how criminals are abusing the system, and using regulatory authorities to proactively mitigate those risks. FinCEN is at its strongest when it uses all of its authorities: law enforcement support, regulatory, international, and networking between government and industry.