Chairman Levin, Ranking Member Camp, and distinguished Members of the Committee, I am Charlie Steele, Deputy Director of the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), and I appreciate the opportunity to appear before you today to discuss the mission and regulatory authorities of FinCEN and to offer some perspectives on potential money laundering vulnerabilities in the traditional, brick-and-mortar gambling industry, which FinCEN has been regulating and proactively analyzing for 15 years, most recently illustrated in the 17th edition of the SAR Activity Review,i published on May 12, 2010 and the basis for much of my testimony today. Although the focus of today’s hearing is on tax perspectives related to internet gambling, as the Members of the Committee know, this particular enterprise has been illegal for many years, and therefore FinCEN has no specific regulatory experience from which to offer viewpoints. However, as the Congress continues to consider legislative proposals impacting the future of internet gambling, our hope is that the information gleaned from our testimony today regarding current trends and typologies will assist your fact-finding and inform future decision making.

Background on FinCEN

FinCEN’s mission is to enhance U.S. national security, detect criminal activity, and safeguard financial systems from abuse by promoting transparency in the U.S. and international financial systems. FinCEN works to achieve its mission through a broad range of interrelated strategies, including:

- Administering the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) - the United States’ primary anti-money laundering/counter-terrorist financing regulatory regime;

- Supporting law enforcement, intelligence, and regulatory agencies through the sharing and analysis of financial intelligence; and

- Building global cooperation and technical expertise among financial intelligence units throughout the world.

To accomplish these activities, FinCEN employs a team comprised of approximately 325 dedicated Federal employees, including analysts, regulatory specialists, international specialists, technology experts, administrators, managers, and Federal agents who fall within one of the following mission areas:

Regulatory Policy and Programs - FinCEN issues regulations, regulatory rulings, and interpretive guidance; coordinates and assists State and Federal regulatory agencies to consistently apply BSA compliance standards in their examination of financial institutions; and takes enforcement action against financial institutions that demonstrate systemic or egregious non-compliance. These activities span the breadth of the financial services industries, including — but not limited to — banks and other depository institutions; money services businesses; securities broker-dealers; mutual funds; futures commission merchants and introducing brokers in commodities; dealers in precious metals, precious stones, or jewels; insurance companies; and casinos.

Analysis and Liaison Services - FinCEN provides Federal, State, and local law enforcement and regulatory authorities with different methods of direct access to reports that financial institutions submit pursuant to the BSA. FinCEN also combines BSA data with other sources of information to produce analytic products supporting the needs of law enforcement, intelligence, regulatory, and other financial intelligence unit customers. Products range in complexity from traditional subject-related research to more advanced analytic work including geographic assessments of money laundering threats.

International Cooperation - FinCEN is one of 116 recognized national financial intelligence units around the globe that collectively constitute the Egmont Group. FinCEN plays a lead role in fostering international efforts to combat money laundering and terrorist financing among these financial intelligence units, focusing our efforts on intensifying international cooperation and collaboration, and promoting international best practices to maximize information sharing.

Background on the Bank Secrecy Act and Filing Requirements

In 1970, Congress passed the Currency and Foreign Transactions Reporting Act, commonly known as the BSA, which authorizes the Secretary of the Treasury to require certain records or reports by private individuals, banks, and other financial institutions where they have a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations or proceedings, or in the conduct of intelligence or counterintelligence activities, including analysis, to protect against international terrorism. The authority of the Secretary to administer the BSA has been delegated to the Director of FinCEN since 1994.

The USA PATRIOT Act of 2001 (USAPA), enacted shortly after the attacks on September 11, 2001, broadened the scope of the BSA to focus on terrorist financing as well as money laundering. The USAPA also gave FinCEN additional responsibilities and authorities in both of these important areas, and formally established the organization as a bureau within the Treasury Department.

Hundreds of thousands of financial institutions are subject to BSA reporting and recordkeeping requirements. These include depository institutions (banks, credit unions and thrifts); brokers or dealers in securities; insurance companies that issue or underwrite certain products; money services businesses (money transmitters; issuers, redeemers and sellers of money orders and travelers’ checks; check cashers and currency exchangers); casinos and card clubs; and dealers in precious metals, stones, or jewels. Below is an outline of the most frequently received forms from a cross-section of industries that fall under the purview of the BSA:

- Currency Transaction Reports (CTRs): CTRs are reports that U.S. financial institutions are required to file for each currency transaction of more than $10,000.

- Currency Transaction Report Casino (CTR-C) CTR-Cs are reports that casinos are required to file for currency transactions in excess of $10,000.

- Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs): SARs are reports filed on transactions or attempted transactions involving at least $5,000 that the financial institution knows, suspects, or has reason to suspect the money was derived from illegal activities, including when transactions are part of a plan to violate Federal laws by circumventing CTR reporting requirements (“structuring” deposits).

- Suspicious Activity Report by Casinos (SAR-C) SAR-Cs are reports filed on transactions or attempted transactions if they are conducted or attempted by, at, or through a casino, and involve or aggregate at least $5,000 in funds or other assets, and the casino/card club knows, suspects, or has reason to suspect that the transactions or pattern of transactions involves funds derived from illegal activities (to include “structuring”)

- Suspicious Activity Report by Money Services Businesses (SAR-MSB): SAR-MSBs are reports filed on transactions or attempted transactions if they are conducted or attempted by, at, or through a Money Services Business (MSB), involve or aggregate funds or other assets of at least $2,000, and the MSB knows, suspects, or has reason to suspect that the transactions or pattern of transactions involves funds derived from illegal activities (to include “structuring”).

- Suspicious Activity Report by the Securities & Futures Industries (SAR-SF): SAR-SFs are reports filed on transactions, or attempted transactions, if they are conducted by, at, or through a broker-dealer, involve aggregate funds or other assets of at least $5,000, and the broker-dealer knows, suspects, or has reason to suspect that the transaction involves funds derived from illegal activities or is intended or conducted in order to hide or disguise funds or assets derived from illegal activity. Also filed when transactions are designed, whether through structuring or other means, to evade filing requirements.

- IRS Form 8300 (8300): 8300s are reports filed by persons engaged in a trade or business who, in the course of that trade or business, receive more than $10,000 in cash in one transaction or two or more related transactions within a twelve month period.

- Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts (FBAR): FBARs are reports filed by individuals to report a financial interest in or signatory authority over one or more accounts in foreign countries, if the aggregate value of these accounts exceeds $10,000 at any time during the calendar year.

Funds Transfer Process – a Brief Overview

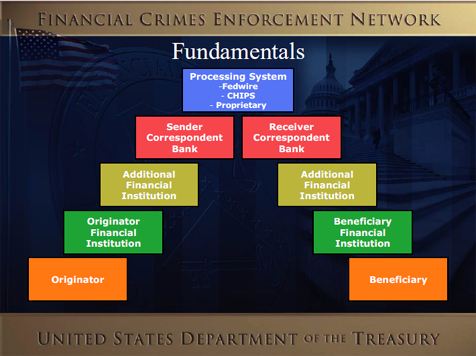

The diagram below generally illustrates how funds transfer transactions flow through a formal channel of multiple intermediary financial institutions -- referred to as correspondent banks --which serve as “building blocks” to connect the originator’s bank with the beneficiary’s bank. If the originator bank and the beneficiary bank do not have a direct correspondent relationship, correspondent banks must become involved to facilitate both the payment instructions and the clearance of funds related to the funds transfer. U.S. banks serving as middle correspondents have a responsibility to monitor and report on suspicious cross-border funds transfers as part of their BSA compliance obligations. Regardless of whether or not there is a direct customer account relationship, if a suspicious funds transfer processes through a U.S.-based bank serving as a middle correspondent, the U.S.-based bank has an obligation to report the transaction through a SAR.

The Value of BSA Data

The financial data collected from financial institutions by FinCEN has proven to be of considerable value in money laundering, terrorist financing and other financial crimes investigations by law enforcement. When combined with other data collected by law enforcement and the intelligence community, BSA data assists investigators in connecting the dots in their investigations by allowing for a more complete identification of the particular subjects with information such as personal information, previously unknown addresses, businesses and personal associations, banking patterns, travel patterns, and communication methods. In fact, according to two reports published by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) examining the usefulness of CTRs and SARs, respectively, both the quality and the use of BSA forms is increasing, and “[i]n addition to supporting specific investigations, CTR requirements aid law enforcement by forcing criminals attempting to avoid reportable transactions to act in ways that increase chances of detection through other methods.”ii Furthermore, the GAO pointed out that “some federal law enforcement agencies have facilitated complex analyses by using SAR data with their own data sets” and that Federal, State, and local law enforcement agencies collaborate to review and start investigations based on SARs filed in their areas."iii

Application of the BSA to the Gambling Industry

State-licensed casinos were made subject to the BSA in 1985 and at the time only two states – Nevada and New Jersey – allowed casinos. Since then the number has grown to more than forty states and many additional tribal casinos. Casinos that are subject to the BSA have an obligation to implement anti-money laundering (AML) programs that include procedures for detecting and reporting suspicious transactions. Casinos are required to implement risk-based AML programs that assist with the identification and reporting of suspicious transactions, including employee training and written procedures on recognizing and addressing signs of suspicious activity and vulnerabilities that may arise through the offering of their particular products and services. Casino employees who monitor customer gambling activity or conduct transactions with customers are in a unique position to recognize transactions and activities that appear to have no legitimate purpose, are not usual for a specific player or type of player, or are not consistent with transactions involving wagering. Many casinos routinely obtain a great deal of information about their customers through deposit, credit, check cashing, player rating and slot club accounts, and these accounts generally require casinos to obtain basic identification information about the accountholders and to inquire into the kinds of wagering activities in which the customer is likely to engage.

The BSA and its implementing regulationsiv define a gambling casino as a financial institution subject to the BSA requirements if it (1) has gross annual gambling revenue of more than $1 million; and (2) is duly licensed as a casino under the laws of a State, territory or possession of the United States; or if it is a tribal gambling operation conducted pursuant to the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) or other Federal, State, or tribal law or arrangement affecting Indian lands, including casinos operating under the assumption or under the view that no such authorization is required for casino operation on Indian lands. For example, tribal gambling establishments that offer slot machines, video lottery terminals, or table games, and that have gross annual gambling revenue in excess of $1 million are covered by the definitions. The definition applies to both land-based and riverboat operations licensed or authorized under the laws of a State, territory, or tribal jurisdiction, or under the IGRA. Card clubs generally are subject to the same rules as casinos, unless a different treatment for card clubs is explicitly stated in the regulations. As stated previously, in addition to other requirements, the implementing regulations require casinos and card clubs to report conducted or attempted transactions or patterns of transactions that the establishment knows, suspects, or has reason to suspect are suspicious and involve or aggregate at least $5,000 in funds or other assets. Nevada casinos began filing reports of suspicious activities under the State’s previous regulatory system in October 1997. Gambling establishments (including State-licensed operations, tribal casinos and card clubs) outside Nevada have been required to report suspicious transactions since March, 2003. From August 1, 1996 through December 31, 2009, casinos and card clubs filed approximately 62,195 suspicious activity reports.

SAR Filing Trends in Casinos

In our most recent analytical study on the gambling industry, FinCEN staff identified 40,409 SAR-Cs filed by casinos and cards clubs from January 1, 2004 through December 31, 2008. These SAR-Cs reported an aggregate of over $900 million of suspicious activity. Although the SAR-Cs examined were filed from 2004 through 2008, some of the suspicious activity began as early as August 2001. Overall, the annual number of SAR-C filings consistently increased during the study time period. The annual dollar amount of the filings, however, has fluctuated from year to year, at times decreasing. For example, while 15 percent of the 40,409 SAR-Cs in our study were filed in 2004, those filings accounted for 12 percent of the total dollar amount reported. In 2005, the percentage of SAR-Cs filed remained at 15 percent, but the percentage of the total dollar amount decreased to 8.5 percent. The last year of our review (2008) reflects the highest percentage of SAR-Cs filed (28 percent), and the percentage of the total dollar amount was nearly 28 percent - a percentage more than two times higher than in 2004. The individual suspicious activity amounts reported in the 40,409 filings ranged from $1 to $50 million; however, 40 percent of the total SAR-Cs provided suspicious activity amounts between $10,001 and $50,000. A breakdown of the filers by States/territories indicates that New Jersey casinos filed the highest number of SAR-Cs (26 percent), while Nevada ranked second on both highest number of filings (18 percent) and dollar amount reported (39 percent).

Factors Triggering a SAR-C

In order to better understand the most common red flags prompting the filing of a SAR-C, FinCEN reviewed the narratives of 2,864 randomly selected SAR-C reports and ascertained that the transactions, activities or behaviors that prompted the filings fell within several categories, which included:

Structuring

Sixty percent of the sampled narratives reported individuals structuring or attempting to structure their transactions to avoid the filing of a CTR-C. Most of the structuring involved the cash-out of chips, jackpots or checks followed by structured cash buy-ins and payments on markers. The key suspicious activities of patrons that casinos observed or detected and reported included:

- Reducing the number of chips or tokens to be cashed out at a cage when asked to provide identification or a SSN when the cash-out was over $10,000, or when a subject had previously cashed out chips or tokens and the additional cash-out would exceed $10,000 in a gambling day (the most reported structuring activity).

- Reducing the amount of cash buy-ins in pits to avoid providing identification or a SSN.

- Using agents to cash out chips.

- Cashing out chips, tickets, and/or tokens multiple times a day at different times or at different windows/cages.

- Requesting jackpot winnings exceeding $10,000 to be paid in two or three checks of lesser value

- Purchasing $9,000 in chips with cash at the cage and purchasing another $1,000 in chips with cash in a pit.

Minimal or No Casino Play

Thirty percent of the sampled narratives reported patrons conducting a series of transactions that involved minimal or no casino play. Specific examples included:

- Cashing out chips when the casino had no record of the individuals having bought or played with chips.

- Buying chips with cash, casino credit, credit card advances, wired funds or funds withdrawn from safekeeping accounts, but playing minimally or not playing at all. The subjects then cashed out the chips or left the casino with unredeemed chips

- Receiving wired funds from a depository institution into an individual’s casino front money account and then requesting that the funds be wired to a another bank account without playing.

- Frequently depositing money orders or casino checks from other casinos into front money accounts, buying in and playing minimally, or not playing and then cashing out through issuance of a casino check.

- Converting currency into redeemable cash tickets by feeding bills (usually $20s) into slot machine bill acceptors, and then printing out TITO ticketsv and cashing out the tickets typically for large denomination bills

Misuse of Identification

Two percent of the reviewed sampled narratives reported subjects misused or attempted to misuse identification by providing false, expired, stolen or altered personal identifiers or identification credentials, mainly SSNs and drivers’ licenses.

Fraud against the Casino

One percent of the sampled narratives indicated fraud or attempted fraud committed against the casinos through checks, counterfeit currency, advance fee scams or misuse of player’s club points. Examples of such fraud included:

- Fraud through checks consisted of payments on markers typically with personal checks that were returned unpaid to a casino due to insufficient funds or accounts closed at depository institutions

- Patrons cashed out or attempted to cash out stolen, forged or altered checks, as well as counterfeited $20 and $100 bills.

Examining Casinos for BSA Compliance and Enforcement Authority

As with depository institutions, the purpose of a BSA casino examination is to determine the adequacy of a casino’s BSA compliance program. FinCEN delegates BSA compliance examination authority to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) for casinos and all other businesses designated as financial institutions under the BSA and its implementing regulations that do not have a Federal regulator. The IRS can conduct examinations to address BSA compliance concerns on a singular, regional or national basis. Casinos have numerous BSA recordkeeping and AML program requirements, and BSA casino examinations include reviewing and analyzing the fulfillment of these obligations as well as identifying any failures to file BSA reports through a risk-based audit plan. A critical process for the IRS in the scoping and planning phase (pre-audit) of a BSA casino examination involves an extensive review and analysis of all BSA reports filed by and on the casino. The review and analysis of the BSA reports filed by the casino is used to determine their adequacy as well as identify trends.

FinCEN is authorized to assess civil money penalties against a casino, card club, or any partner, director, officer, or employee thereof, for willful violations of BSA anti-money laundering program, reporting, and recordkeeping requirements, as follows:

- A penalty of $25,000 per day may be assessed for failure to establish and implement an adequate written BSA compliance or anti-money laundering program, including program failures that led to instances of undetected structuring. A separate violation occurs for each day the violation continues.

- A penalty not to exceed the greater of the amount involved in the transaction (but capped at $100,000) or $25,000 may

- A penalty up to the amount of the coins and currency involved in the transaction[s] for structuring, attempting to structure, or assisting in structuring.

Conclusion

FinCEN remains committed to protecting the financial system from abuse by criminals, and we will continue to engage the gambling industry not only by providing useful information and guidance to help them focus their compliance efforts against actual risks, but to continue our ongoing and coordinated educational efforts to better inform the industry so that gambling interests have the latest information they need to comply with the BSA, and ultimately, help law enforcement identify and stop illicit activity. Thank you for inviting me to testify, and I would be happy to answer any questions.