Chairman Carper, Ranking Member Coburn, and distinguished Members of the Committee, I am Jennifer Shasky Calvery, Director of the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), and I appreciate the opportunity to appear before you today to discuss FinCEN’s ongoing role in the Administration’s efforts to establish a meaningful regulatory framework for virtual currencies that intersect with the U.S. financial system. We appreciate the Committee’s interest in this important issue, and your continued support of our efforts to prevent illicit financial activity from exploiting potential gaps in our regulatory structure as technological advances create new and innovative ways to move money. I am also pleased to be testifying with my colleagues from the Departments of Justice and Homeland Security. Both play an important role in the global fight against money laundering and terrorist financing, and our collaboration on these issues greatly enhances the effectiveness of our efforts.

FinCEN’s mission is to safeguard the financial system from illicit use, combat money laundering and promote national security through the collection, analysis, and dissemination of financial intelligence and strategic use of financial authorities. FinCEN works to achieve its mission through a broad range of interrelated strategies, including:

- Administering the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) - the United States’ primary anti-money laundering (AML)/counter-terrorist financing (CFT) regulatory regime;

- Sharing the rich financial intelligence we collect, as well as our analysis and expertise, with law enforcement, intelligence, and regulatory partners; and,

- Building global cooperation and technical expertise among financial intelligence units throughout the world.

To accomplish these activities, FinCEN employs a team comprised of approximately 340 dedicated employees with a broad range of expertise in illicit finance, financial intelligence, the financial industry, the AML/CFT regulatory regime, technology, and enforcement. We also leverage our close relationships with regulatory, law enforcement, international, and industry partners to increase our collective insight and better protect the U.S. financial system.

What is Virtual Currency?

Before moving into a discussion of FinCEN’s role in ensuring we have smart regulation for virtual currency that is not too burdensome but also protects the U.S. financial system from illicit use, let me set the stage with some of the definitions we are using at FinCEN to understand virtual currency and the various types present in the market today. Virtual currency is a medium of exchange that operates like a currency in some environments but does not have all the attributes of real currency. In particular, virtual currency does not have legal tender status in any jurisdiction. A convertible virtual currency either has an equivalent value in real currency, or acts as a substitute for real currency. In other words, it is a virtual currency that can be exchanged for real currency. At FinCEN, we have focused on two types of convertible virtual currencies: centralized and decentralized.

Centralized virtual currencies have a centralized repository and a single administrator. Liberty Reserve, which FinCEN identified earlier this year as being of primary money laundering concern pursuant to Section 311 of the USA PATRIOT Act, is an example of a centralized virtual currency. Decentralized virtual currencies, on the other hand, and as the name suggests, have no central repository and no single administrator. Instead, value is electronically transmitted between parties without an intermediary. Bitcoin is an example of a decentralized virtual currency. Bitcoin is also known as cryptocurrency, meaning that it relies on cryptographic software protocols to generate the currency and validate transactions.

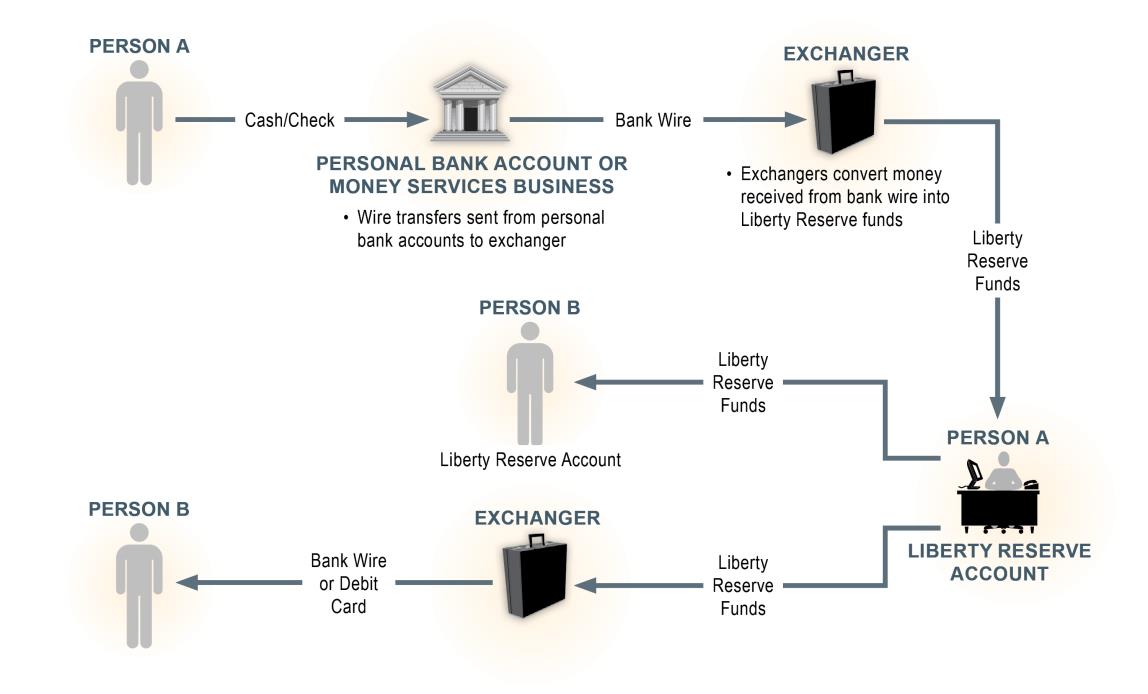

There are a variety of methods an individual user might employ to obtain, spend, and then “cash out” either a centralized or decentralized virtual currency. The following illustration shows a typical series of transactions in a centralized virtual currency, such as Liberty Reserve:

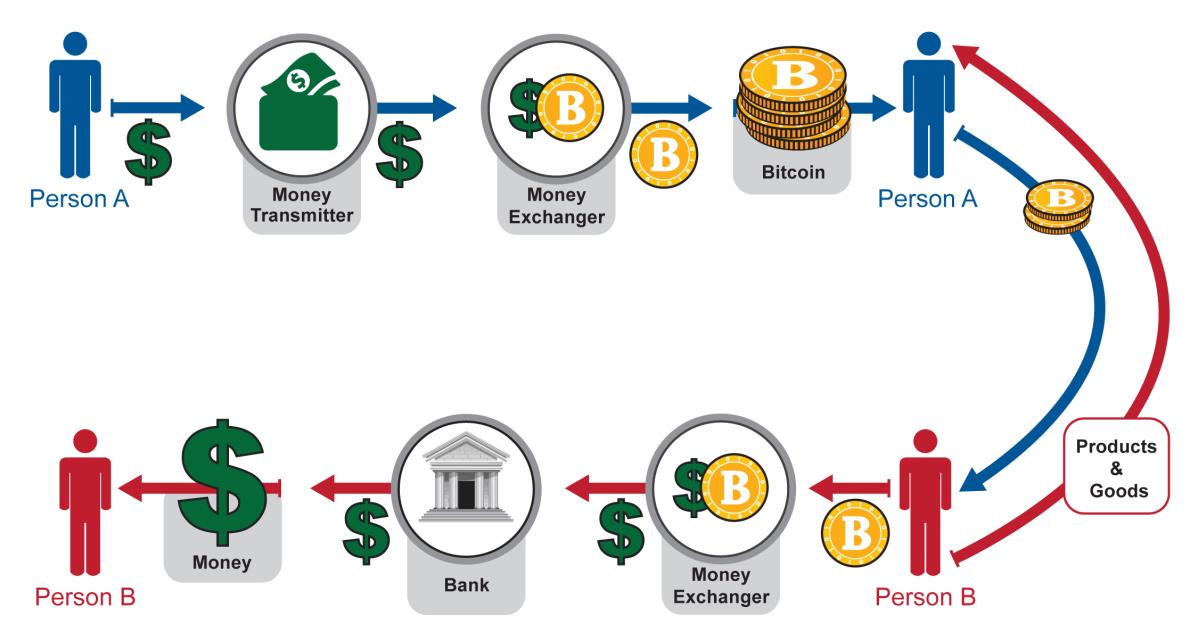

By way of comparison, the next illustration shows a very similar series of transactions in a decentralized virtual currency such as Bitcoin:

From a “follow the money” standpoint, the main difference between these two series of transactions is the absence of an “administrator” serving as intermediary in the case of Bitcoin. This difference does have significance in FinCEN’s regulatory approach to virtual currency, and that approach will be addressed further during the course of my testimony today.

Money Laundering Vulnerabilities in Virtual Currencies

Any financial institution, payment system, or medium of exchange has the potential to be exploited for money laundering or terrorist financing. Virtual currency is not different in this regard. As with all parts of the financial system, though, FinCEN seeks to understand the specific attributes that make virtual currency vulnerable to illicit use, so that we can both employ a smart regulatory approach and encourage industry to develop mitigating features in its products.

Some of the following reasons an illicit actor might decide to use a virtual currency to store and transfer value are the same reasons that legitimate users have, while other reasons are more nefarious. Specifically, an illicit actor may choose to use virtually currency because it:

- Enables the user to remain relatively anonymous;

- Is relatively simple for the user to navigate;

- May have low fees;

- Is accessible across the globe with a simple Internet connection;

- Can be used both to store value and make international transfers of value;

- Does not typically have transaction limits;

- Is generally secure;

- Features irrevocable transactions;

- Depending on the system, may have been created with the intent (and added features) to facilitate money laundering;

- If it is decentralized, has no administrator to maintain information on users and report suspicious activity to governmental authorities;

- Can exploit weaknesses in the anti-money laundering/counter terrorist financing (AML/CFT) regimes of various jurisdictions, including international disparities in, and a general lack of, regulations needed to effectively support the prevention and detection of money laundering and terrorist financing.

Because any financial institution, payment system, or medium of exchange has the potential to be exploited for money laundering, fighting such illicit use requires consistent regulation across the financial system. Virtual currency is not different from other financial products and services in this regard. What is important is that financial institutions that deal in virtual currency put effective AML/CFT controls in place to harden themselves from becoming the targets of illicit actors that would exploit any identified vulnerabilities.

Indeed, the idea that illicit actors might exploit the vulnerabilities of virtual currency to launder money is not merely theoretical. We have seen both centralized and decentralized virtual currencies exploited by illicit actors. Liberty Reserve used its centralized virtual currency as part of an alleged $6 billion money laundering operation purportedly used by criminal organizations engaged in credit card fraud, identity theft, investment fraud, computer hacking, narcotics trafficking, and child pornography. One Liberty Reserve co-founder has already pleaded guilty to money laundering in the scheme. And just recently, the Department of Justice has alleged that customers of Silk Road, the largest narcotic and contraband marketplace on the Internet to date, were required to pay in bitcoins to enable both the operator of Silk Road and its sellers to evade detection and launder hundreds of millions of dollars. With money laundering activity already valued in the billions of dollars, virtual currency is certainly worthy of FinCEN’s attention.

That being said, it is also important to put virtual currency in perspective as a payment system. The U.S. government indictment and proposed special measures against Liberty Reserve allege it was involved in laundering more than $6 billion. Administrators of other major centralized virtual currencies report processing similar transaction volumes to what Liberty Reserve did. In the case of Bitcoin, it has been publicly reported that its users processed transactions worth approximately $8 billion over the twelve-month period preceding October 2013; however, this measure may be artificially high due to the extensive use of automated layering in many Bitcoin transactions. By way of comparison, according to information reported publicly, in 2012 Bank of America processed $244.4 trillion in wire transfers, PayPal processed approximately $145 billion in online payments, Western Union made remittances totaling approximately $81 billion, the Automated Clearing House (ACH) Network processed more than 21 billion transactions with a total dollar value of $36.9 trillion, and Fedwire, which handles large-scale wholesale transfers, processed 132 million transactions for a total of $599 trillion. This relative volume of transactions becomes important when you consider that, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the best estimate for the amount of all global criminal proceeds available for laundering through the financial system in 2009 was $1.6 trillion. While of growing concern, to date, virtual currencies have yet to overtake more traditional methods to move funds internationally, whether for legitimate or criminal purposes.

Mitigating Money Laundering Vulnerabilities in Virtual Currencies

FinCEN’s main goal in administering the BSA is to ensure the integrity and transparency of the U.S. financial system so that money laundering and terrorist financing can be prevented and, where it does occur, be detected for follow on action. One of our biggest challenges is striking the right balance between the costs and benefits of regulation. One strategy we use to address this challenge is to promote consistency, where possible, in our regulatory framework across different parts of the financial services industry. It ensures a level playing field for industry and minimizes gaps in our AML/CFT coverage.

Recognizing the emergence of new payment methods and the potential for abuse by illicit actors, FinCEN began working with our law enforcement and regulatory partners several years ago to study the issue. We understood that AML protections must keep pace with the emergence of new payment systems, such as virtual currency and prepaid cards, lest those innovations become a favored tool of illicit actors. In July 2011, after a public comment period designed to receive feedback from industry, FinCEN released two rules that update several definitions and provide the needed flexibility to accommodate innovation in the payment systems space under our preexisting regulatory framework. Those rules are: (1) Definitions and Other Regulations Relating to Money Services Businesses; and (2) Definitions and Other Regulations Relating to Prepaid Access.

The updated definitions reflect FinCEN’s earlier guidance and rulings, as well as current business operations in the industry. As such, they have been able to accommodate the development of new payment systems, including virtual currency. Specifically, the new rule on money services businesses added the phrase “other value that substitutes for currency” to the definition of “money transmission services.” And since a convertible virtual currency either has an equivalent value in real currency, or acts a substitute for real currency, it qualifies as “other value that substitutes for currency” under the definition of “money transmission services.” A person that provides money transmission services is a “money transmitter,” a type of money services business already covered by the AML/CFT protections in the BSA.

As a follow-up to the regulations and in an effort to provide additional clarity on the compliance expectations for those actors involved in virtual currency transactions subject to FinCEN oversight, on March 18, 2013, FinCEN supplemented its money services business regulations with interpretive guidance designed to clarify the applicability of the regulations implementing the BSA to persons creating, obtaining, distributing, exchanging, accepting, or transmitting virtual currencies. In the simplest of terms, FinCEN’s guidance explains that administrators or exchangers of virtual currencies must register with FinCEN, and institute certain recordkeeping, reporting and AML program control measures, unless an exception to these requirements applies. The guidance also explains that those who use virtual currencies exclusively for common personal transactions like buying goods or services online are users, not subject to regulatory requirements under the BSA. In all cases, FinCEN employs an activity-based test to determine when someone dealing with virtual currency qualifies as a money transmitter. The guidance clarifies definitions and expectations to ensure that businesses engaged in such activities are aware of their regulatory responsibilities, including registering appropriately. Furthermore, FinCEN closely coordinates with its state regulatory counterparts to encourage appropriate application of FinCEN guidance as part of the states’ separate AML compliance oversight of financial institutions.

It is in the best interest of virtual currency providers to comply with these regulations for a number of reasons. First is the idea of corporate responsibility. Legitimate financial institutions, including virtual currency providers, do not go into business with the aim of laundering money on behalf of criminals. Virtual currencies are a financial service, and virtual currency administrators and exchangers are financial institutions. As I stated earlier, any financial institution could be exploited for money laundering purposes. What is important is for institutions to put controls in place to deal with those money laundering threats, and to meet their AML reporting obligations.

At the same time, being a good corporate citizen and complying with regulatory responsibilities is good for a company’s bottom line. Every financial institution needs to be concerned about its reputation and show that it is operating with transparency and integrity within the bounds of the law. Legitimate customers will be drawn to a virtual currency or administrator or exchanger where they know their money is safe and where they know the company has a reputation for integrity. And banks will want to provide services to administrators or exchangers that show not only great innovation, but also great integrity and transparency.

The decision to bring virtual currency within the scope of our regulatory framework should be viewed by those who respect and obey the basic rule of law as a positive development for this sector. It recognizes the innovation virtual currencies provide, and the benefits they might offer society. Several new payment methods in the financial sector have proven their capacity to empower customers, encourage the development of innovative financial products, and expand access to financial services. We want these advances to continue. However, those institutions that choose to act outside of their AML obligations and outside of the law have and will continue to be held accountable. FinCEN will do everything in its regulatory power to stop such abuses of the U.S. financial system.

As previously mentioned, earlier this year, FinCEN identified Liberty Reserve as a financial institution of primary money laundering concern under Section 311 of the USA PATRIOT Act. Liberty Reserve operated as an online, virtual currency, money transfer system conceived and operated specifically to allow – and encourage – illicit use because of the anonymity it offered. It was deliberately designed to avoid regulatory scrutiny and tailored its services to illicit actors looking to launder their ill-gotten gains. According to the allegations contained in a related criminal action brought by the U.S. Department of Justice, those illicit actors included criminal organizations engaged in credit card fraud, identity theft, investment fraud, computer hacking, narcotics trafficking, and child pornography, just to name a few. The 311 action taken by FinCEN was designed to restrict the ability of Liberty Reserve to access the U.S. financial system, publicly notify the international financial community of the risks posed by Liberty Reserve, and to send a resounding message to other offshore money launderers that such abuse of the U.S. financial system will not be tolerated and their activity can be reached through our targeted financial measures.

Sharing Our Knowledge and Expertise on Virtual Currency

As the financial intelligence unit for the United States, FinCEN must stay current on how money is being laundered in the United States, including through new and emerging payment systems, so that we can share this expertise with our many law enforcement, regulatory, industry, and foreign financial intelligence unit partners, and effectively serve as the cornerstone of this country’s AML/CFT regime. FinCEN has certainly sought to meet this responsibility with regard to virtual currency and its exploitation by illicit actors. In doing so, we have drawn and continue to draw from the knowledge we have gained through our regulatory efforts, use of targeted financial measures, analysis of the financial intelligence we collect, independent study of virtual currency, outreach to industry, and collaboration with our many partners in law enforcement.

In the same month we issued our guidance on virtual currency, March 2013, FinCEN also issued a Networking Bulletin on crypto-currencies to provide a more granular explanation of this highly complex industry to law enforcement and assist it in following the money as it funnels between virtual currency channels and the U.S. financial system. Among other things, the bulletin addresses the role of traditional banks, money transmitters, and exchangers that come into play as intermediaries by enabling users to fund the purchase of virtual currencies and exchange virtual currencies for other types of currency. It also highlights known records processes associated with virtual currencies and the potential value these records may offer to investigative officials. The bulletin has been in high demand since its publication and the feedback regarding its tremendous value has come from the entire spectrum of our law enforcement partners. In fact, demand for more detailed information on crypto-currencies has been so high that we have also shared it with several of our regulatory and foreign financial intelligence unit partners.

One feature of a FinCEN Networking Bulletin is that it asks the readers to provide ongoing feedback on what they are learning through their investigations so that we can create a forum to quickly learn of new developments, something particularly important with a new payment method. Based on what we are learning through this forum and other means, FinCEN has issued several analytical products of a tactical nature to inform law enforcement operations.

Equally important to our ongoing efforts to deliver expertise to our law enforcement partners is FinCEN’s engagement with our regulatory counterparts to ensure they are kept apprised of the latest trends in virtual currencies and the potential vulnerabilities they pose to traditional financial institutions under their supervision. FinCEN uses its collaboration with the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) BSA Working Group as a platform to review and discuss FinCEN’s regulations and guidance, and the most recent and relevant trends in virtual currencies. One such example occurred just recently, when several FinCEN virtual currency experts gave a comprehensive presentation on the topic to an audience of Federal and state bank examiners at an FFIEC Payment Systems Risk Conference. The presentation covered an overview of virtual currency operations, FinCEN’s guidance on the application of FinCEN regulations to virtual currency, enforcement actions, and ongoing industry outreach efforts.

FinCEN also participates in the FBI-led Virtual Currency Emerging Threats Working Group, the FDIC-led Cyber Fraud Working Group, the Terrorist Financing & Financial Crimes-led Treasury Cyber Working Group, and with a community of other financial intelligence units. We host speakers, discuss current trends, and provide information on FinCEN resources and authorities as we work with our partners in an effort to foster an open line of communication across the government regarding bad actors involved in virtual currency and cyber-related crime.

Finally, FinCEN has shared its strategic analysis on money laundering through virtual currency with executives at many of our partner law enforcement and regulatory agencies, and foreign financial intelligence units, as well as with U.S. government policy makers.

Outreach to the Virtual Currency Industry

Recognizing that the new, expanded definition of money transmission would bring new financial entities under the purview of FinCEN’s regulatory framework, shortly after the publication of the interpretive guidance and as part of FinCEN’s ongoing commitment to engage in dialogue with the financial industry and continually learn more about the industries that we regulate, FinCEN announced its interest in holding outreach meetings with representatives from the virtual currency industry. The meetings are designed to hear feedback on the implications of recent regulatory responsibilities imposed on this industry, and to receive industry’s input on where additional guidance would be helpful to facilitate compliance.

We held the first such meeting with representatives of the Bitcoin Foundation on August 26, 2013 at FinCEN’s Washington, DC offices and included attendees from a cross-section of the law enforcement and regulatory communities. This outreach was part of FinCEN’s overall efforts to increase knowledge and understanding of the regulated industry and how its members are impacted by regulations, and thereby help FinCEN most efficiently and effectively work with regulated entities to further the common goals of the detection and deterrence of financial crime. To further capitalize on this important dialogue and exchange of ideas, FinCEN has invited the Bitcoin Foundation to provide a similar presentation at the next plenary of the Bank Secrecy Act Advisory Group (BSAAG) scheduled for mid-December. The BSAAG is a Congressionally-chartered forum that brings together representatives from the financial industry, law enforcement, and the regulatory community to advise FinCEN on the functioning of our AML/CFT regime.

Conclusion

The Administration has made appropriate oversight of the virtual currency industry a priority, and as a result, FinCEN’s efforts in this regard have increased significantly over recent years through targeted regulatory measures, outreach to regulatory and law enforcement counterparts and our partners in the private sector, and the development of expertise. We are very encouraged by the progress we have made thus far. We are dedicated to continuing to build on these accomplishments by remaining focused on future trends in the virtual currency industry and how they may inform potential changes to our regulatory framework for the future. Thank you for inviting me to testify before you today. I would be happy to answer any questions you may have.